By Sierah Tyson

The Winter 2018 Standards Institute continued a movement. For five days, participants dove deep into the language of the standards, collaborated with educators outside their networks, evaluated instructional practices, and examined the systems they serve. Here are my five biggest takeaways from those five days.

This winter was my fourth Standards Institute, and it continues to be an honor to work and learn alongside such talented and dedicated educators. Whether you attended this Institute or not, I hope this reflection helps you start—or continue—critical conversations about education and the ways we approach it.

1. We are the system

The opening keynote address started the week with the poignant phrase: “We are the system.” We can no longer blame others for what is happening in education because we each play a significant role in the system. That means if we are not happy with the results this system produces, we must do our part in reimagining and restructuring it. To do that, we have to take time to recognize and reflect on the bias and inequities within ourselves, our practice, our schools, and in the systems we serve. When we don’t recognize or address these inequities, we end up perpetuating them. Here are some of the questions that helped us reflect on these issues at Standards Institute:

Where are our conscious or unconscious biases? Do we value all students equally? Whom do we have more patience for? Whom do our scaffolds support? Whom do we consider to be gifted and talented? Which students are typically awarded advanced placement status? Who is most often referred to special education? Who is disproportionately expelled and suspended for minor infractions? Why are students of color disproportionately failing? How does this disparity impact our education system? What does the research say? What power do we have to change the system?

Standards Institute helped participants find language and tools they could use to confront bias within themselves, their instruction, and the systems they serve. For more information on ways to recognize, respond to, and redress bias, consider adding “Equity Literacy for All” by Paul C. Gorski and Katy Swalwell to your reading list.

2. Different perspectives add value to the conversation

This Standards Institute brought together more than 800 participants from 24 states and 96 school systems. These participants educate more than 4 million students. This five-day Institute was meaningful because we all came with varied knowledge and diverse perspectives. Robert John Meehan, a former teacher, and author, says, “The most valuable resource that all teachers have is each other. Without collaboration, our growth is limited to our own perspective.” The variety of perspectives and backgrounds, coupled with norming to create a safe environment, led to lively discussions about content and courageous conversations around equity. From superintendents and teachers to instructional coaches, students, and parents, these different perspectives, especially those that have been historically left out, must be part of the conversation if we want to make informed, impactful changes.

A charge to you: Ask questions or share what you know. You can join the conversation on Twitter or join our growing community on Facebook. Also, consider adding Glenn E. Singleton’s Courageous Conversations About Race: A Field Guide for Achieving Equity in Schools to your reading list for more ways to support and engage in conversations about race and equity.

3. Equity and standards must work together

At Standards Institute, I met educators who were either comfortable with the standards or comfortable with equitable practices in the classroom. But to be effective, educators must bring these ideas together. During Institute, we worked with educators to explore the intersection of the standards-content-aligned curriculum and equitable instructional practices. It was hard work and we uncovered questions like “how often do you talk about both standards-aligned curriculum and equitable instructional practices?” Hopefully, often because they are both essential in closing the opportunity gaps, but for many, this is not the case.

Equity means advancing students’ learning by giving them what they need, and having a standards-aligned curriculum moves us in that direction. But is it enough? The power of an aligned curriculum can fall short when personal biases and/or inequitable instructional practices become roadblocks for students. While equitable instructional practices can serve student’s needs, they alone will not help students make necessary gains if they are not paired with an aligned curriculum. We can no longer look at these issues in isolation or cling to one and not the other. They are very much connected, and change happens at the intersection of the two.

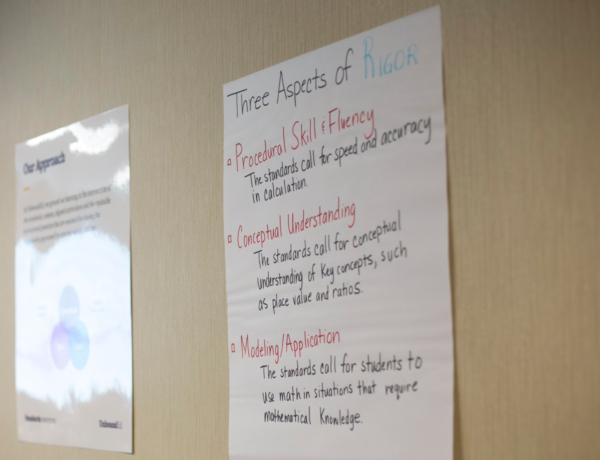

4. Teachers need productive struggle too

In a previous blog, we discussed the importance of becoming comfortable placing our students into a productive struggle, but a struggle is not just for them. As educators, we must engage in a productive struggle to continue to improve our practice and push our thinking. At Standards Institute, educators engaged in productive struggle around the language of the standards and what they call for, the adaptive change required in order to commit to the shifts, and personal biases that may get in the way of instruction.

I noticed a flush of uncertainty on many faces when we entered those moments of productive struggle. I think that uncertainty stems from the myth that teachers are supposed to have all the answers. But part of learning and growing our practice involves realizing that it’s okay to not know the answer all the time. And when we are unsure, we should take the time to grapple with tough questions, study the research about what works for students, discuss our findings with our colleagues, and continue to practice different strategies. The problems we face will not have simple answers, nor will the first strategy always work. We have to continue building our stamina for problem-solving by engaging in productive struggle.

5. Our students are capable

Educators systemically underestimate what our students are capable of achieving. While this may happen with the greatest of intentions, it does not serve our students. We have to stop setting these low expectations.

Lakisha Covert, Director of Engagement at UnboundEd says, “When students are in the classroom, they are at the mercy of what their teachers think they can handle.” We have to believe that students are capable of doing the work, and that starts with looking at our own beliefs and practices. If we want to provide students with what they need to be successful in five, 10, or 30 years, we have to constantly grapple with these questions: “Who is the level of challenge in my classroom serving? Is it in the best interest of me [the teacher] or my students?” If we have low expectations for our students, we rob them of the instructional opportunities, skills, and tools necessary to compete, survive, and thrive in an ever-changing and demanding job market. Watch Lacey Robinson close out the week with a powerful keynote that reminds us to ground our work in what is best for our students.

Let’s continue the conversation! What did you learn at Standards Institute? What questions do you still have? The theme of Winter Standards Institute 2018 was “know more, do better,” taken from a well-known Dr. Maya Angelou quote. The full text is, “I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.” What is it that you know more of and how are you planning to do better? Follow me at @educationNomad and let’s talk!

Looking forward to seeing you at the next Standards Institute, which will be held in San Diego, California, July 9–13.